The body of work to which this simple passage is found delicately stapled was executed as an effort to recognize and to harness the dual importance of artist and viewer in these flights of fancy (not sure I like this phrasing). While unfettered creativity is still essential, identification is no longer my foe. Counter to past concern, imaginative potential has not been compromised in this heady undertaking. A cycle between words and imagery was easily and organically established, between action and assessment. A number of numbered “thought-diagrams” were constructed in conjunction with two-dimensional “illustrative” compositions. Some diagrams precede their compositional counterparts, while others step in at the middle and end of production, respectively. At times the creamy off-colored squares resemble simple drills of word-association while others go a bit deeper. Semi-conscious observations otherwise ignored stand to be counted in sprouting bursts of verbal digressions. Their function is neither one of interchangeability nor one of opposition. They are imaginative investigations in their own right. Drawings, diagrams and other incidentals combine to provide a visible progression; each advancing object/element is composed of preceding parts.

These objects are not in the business of conclusiveness. Answers stifle upon premature arrival; inquisition is essential to discovery. It is inquiry that maintains a fluidity of thinking. Me? I am but a lone defender of imagination, both yours and mine. My goal is not to dictate, but to foster.

Besides, art need not be a drag.

Friday, October 1, 2010

Thesis: Final First Draft, 11 is a lucky number

There is a growing bleakness slowly swaddling this particular epoch of humankind; my generation is far too comfortable with the term “Apocalypse”. Rather than clutter my process with the density of distress, I allow art to be a true act of optimism in my life, even if what is produced is nor purely optimistic. Escapist as it may seem, the thing I love best about art is the plentiful cornucopia of possibilities it presents. My daily life is composed of a number of seemingly shock-less objects and habits; creating constructs an opportunity to expand and forge far beyond the trappings of the known and accepted. In many cases that which is presumed known is rediscovered in a fantastical new light.

As an artist privileged enough to be making work in 2010, where opportunity is vast and experimentation is commended, why would I constrict my heart’s content? Life can’t help but be limited; poverty limits us farther. The laws of both society and physics are to be followed, lest one suffer the consequences. In the second- dimension, such laws are not easily punishable or applicable. So why not take up this one chance and plunge forth into possibilities not offered in our own realm, the one called life?

This declaration of allegiance to the fantastical is my privilege as an artist of this epoch; it is also bit of a conceit.

These sentiments glisten and glow in the soft wattage of generality. Theirs is a vague glory; verbal ventures into specificity (of execution and effect) mostly die upon the page and tongue…and so I refuse. “Words fail! Words limit! Experience for yourself!” I cry. This response never goes over well. The phrase “cop out” emerges to rear its ugly and not so unanticipated head, as do the words “childish”, “flippant”, and (my favorite) “irresponsible”. Choices made in the heat of the making-moment become seemingly arbitrary in their unstructured push for possibility, once extracted from any effort towards explanation. It would seem that no matter how affecting these artistic vagaries may perform in practice, declarative matches for How and Why remain requisites. My quandary is in no way novel; the epic low-grade struggle of The Artist between words and wares long precedes this baby-faced millennium. More akin to repetitious trips to a crowded grocery store than a tumultuous10-year excursion from Troy to Ithaca, the task is brow-drenching all the same. My own explicative efforts have almost always fallen short of both adequacy and success. Inky droplets wrung from mangled missives stain these hands time and again.

Are these splashy sashays into imagination so light as to be content free? Can that which is born from a near monastic studio practice have much to offer the outside world and its inhabitants? Art is a form of communication, after all. If the artist and creator is loath to identify meaning within her work, how then can a viewer be expected to do so? This ever-maddening linguistic situation, of warring words and imagery, poses a paradox to my production. Be that as it may, the potential frivolity (and inaccessibility) of my artistic devotion is not easily digested. Expansion, with a dash of intimacy, is my prime objective; these intrigues of the imagination are meant as joint ventures. Without words, these products of secluded thoughts and actions are forced to teeter towards exclusion rather than invitation. If left in this fugue state of experimentation, indulgence may be only mine alone.

Dictionaries flip and offer me their contents. For years the word “surreal” has been under my clumsy employ, summoned dutifully for explanatory endeavors both great and small. It always seemed the best emissary to the oddball imagery born from my rampant acts of imagination. Of course the word had been produced with little conscious regard or respect for all that word implies. It was a term chosen more out of exasperation than laziness, I swear. Now a few years older and wiser(-ish), I’ve discovered that intuition goes a little farther towards actually accounting for my practice in action, as well as my verbal blockages. Random House has intuition listed as:

1. knowledge or belief obtained neither by reason nor by perception 2. instinctive knowledge or belief 3. a hunch, or unjustified belief

Initially these words combine to create a swagger—a sort of confidence despite nebulous conditions. The word knowledge works to assuage any wrinkles of concern creasing this crumpled brow, to squelch reason’s reproachful glare. Unfortunately, these words act as double agents, operating both for and against my argument. Belief does not belie truth, reason or sanity. As for hunch, well, need I say more? How can you trust a hunch to do the heavy lifting?

A year or two ago, while in the throes of an era far from digital technology and plastic (I was researching Renoir), I found my state disrupted when a good friend demanded that I watch a particular episode of Art:21. I protested, crying “Impressionism!”; she plunked me into a chair and cued up. As soon as the name “Jessica Stockholder” crossed the screen, a burst of recognition followed. A professor had recommended I look at Stockholder when I’d been going through a thoroughly embarrassing and brief installation phase. Though my current work is quite different than that of Jessica Stockholder, our sensibilities regarding creativity and creation seem quite similar.

What’s intuition? It’s a kind of thinking. It’s not stupidity…I think there’s a discomfort associated with trying to put (together) all those different ways…the brain works. I like to avail myself of that discomfort. (Stockholder, PBS)

Stockholder describes her artistic process as an act of “play”, a process of “learning and thinking” with “no pre-determinate end”(Stockholder, PBS). Her installations consist of everyday objects, and are heavily dependent upon lots of brightly colored plastic. In some cases the objects hold weightier metaphoric meanings. The piece she was working on in this particular episode involved freezers. To Stockholder, the freezers carry a “dual” meaning. On one hand they are “places of food” and food can be symbolic of “family, loving, giving”. At the same time the freezer is “cold” which related to withholding.

Her process of color arrangement is quite painterly. Her aptly titled #291 is composed of “acrylic and oil paints, couch cushions, plastic container lid, shoe laces, hardware, chain, plastic scoop and toilet plunger” (McSweeney, http://www.virginia.edu/); a blend of bright blues, oranges, pinks and greens that are both flat and sculptural. Though I was only able to get a digital glimpse of this piece; 291’s ’s object-ness has not been lost or leveled. I am taken in and out of the second and third dimension quite organically. A cushion hangs from the wall, with a segmented plastic container attached to the lower left side. Orange scoops are grouped, spilling out of this plastic container. A chain extends out from the left of the scoops as a blue toilet plunger sits on the right. At the end of the disc is a circle of what looks like metal but it most likely paint. The container-cushion configuration is painted in segments of bold, flat tones; thus aiding in the flatting of the total composition into a cohesive whole. Just as that particular area reads as flat, I’m brought back into the clever little scoops.

The objects move between actuality, representation/symbolism (at times) and sheer forms and fields of color. There are a few tiers of material function and interplay at work. 291pulls me from its formal elements out into a quirky narrative, and then back into its aesthetic composition cyclically. At times I see a little moonscape and/or Mars-Lander, complete with it’s own chained metallic moon/planet. As soon as I get comfortable with this landscape, the toilet plunger declares itself a toilet plunger and I am on Earth once more. Stockholder does not seek to fully control how these objects are perceived, though she is aware of their power. They provide formal pleasures while simultaneously pointing to the real world. She attempts to create another world of experience, fantastical and free from the mundane, out of thoroughly mundane objects. This transformation allows us to be transported, elevated.

…my impulse to make a work begins with my feeling that emotional life isn’t allowed room in the world. This feeling is personal to me and my history, but I think it is also a modern issue in that a lot of people share those worries and feelings. So my work becomes a place to make fantasy and emotional life as concrete and real and important as a refrigerator, or the room that you are in. (Westfall, http://bombsite.com/issues/41/articles/1576)

I’d say there are two major differences between Stockholder’s work and my own. First, I do not stray too far from the second dimension. Although I utilize a variety of common materials in my craft (from jeans to table tops), the predominant amount of my work’s action occurs as surface-focused lines and color. “Real-world” materials are essential to my studio practice but the hierarchy of importance between object, representation and form is balanced somewhat differently than Stockholder’s. I don’t believe a two-dimensional art object can be taken without some consideration to matter and material. A painting refers to at least two realities: material and representational. As crucial as this idea of materiality and recycling is to my work (and life), it is not the sole epicenter of meaning.

The second major difference between Stockholder and I is that make use representational imagery, while she avoids it.

For me, to the extent that the work is abstract and not literal or literary, it is freed up to say something. I feel trapped by the literary. I think I would feel my work more subject to degradation or emptying out if I were making figurative work. Things that are abstract have the possibility to include different ways of thinking. (Westfall, http://bombsite.com/issues/41/articles/1576)

While Stockholder fears “figuration” would lead to limitation, I’d argue encroachment is not inevitable. One can use representational imagery in a non-specific, non-literal way. The people I paint are both unreal and totally real. Stockholder refers to the literary and literal in conjunction to figuration, I do not think that’s an inevitable anchor; it simply depends on the artist’s ability to allow for specificity beyond intention. Neo Rauch is an excellent example of this sort of practice: the use of representational imagery free from the constraints of straight narrative. In his article regarding Rauch’s interesting ascent into the “illustrious line of contemporary German artists,” Gregory Volk makes flagrant use of the words “maybe” and “might.”

Maybe [Tal] was meant as an ironic send-up of the former East-German government’s obsession with athleticism as a symbol of socialist prowess—but then again, maybe not (Volk, 140)

[Rauch’s paintings] might be triggered by details in and around Leipzig, or by childhood memories and, as he has occasionally indicated dreams, but their reach is in a collective past toward a speculative dream. (Volk, 140)

Volk is careful to keep his tentative translation of Rauch’s work in an amorphous state, though the imagery is well defined. That Volk is hesitant to charge full-force into a detailed assessment metaphor and meaning is a care I greatly appreciate. An application of steadfast subtext to each and every figure and symbol would stand in opposition to Rauch’s practice. When asked “about the meaning of his characters”(Volk, 142) at particular public engagement, Rauch “candidly admitted that he couldn’t always say for sure, but sometimes his figures are there simply because the picture requires it”(Volk, 142). Volk describes Rauch as abstractionist as much as a realist, “developing and positioning figures as much as an abstract painter works with basic formal elements”(Volk, 142). It’s not that the work is devoid of meaning, limited to pure formalism.

His symbolism, if indeed it is symbolism, is too hermetic, his references too complex…so you give yourself up to his paintings, approaching them with something of bewilderment. (Volk, 142)

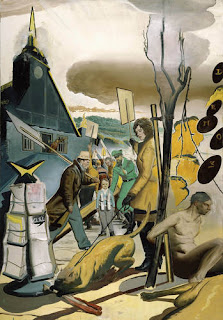

Rauch’s Demos, at first glance, certainly emits a sort of Socialist mustiness. A number of sign wielding protesters spill back into space, a soldier in green makes a grab at a small child who looks directly out of the composition. The coloring is a bit paired down, compared to Rauch’s other works. It is the female figure at the center of the composition that drags me out of such a literal, slightly political reading. She is dressed in contemporary clothes; she wears black leather high-heeled boots and what looks to be a fashionable yellowish-tan overcoat. Her hair is stylishly layered; she holds a leash in one hand, and a sign in the other. Her dog pulls at the leash and bends to chew at a strange bone; a canine echo appears at the right hand corner of the composition in the form of a hind leg. The letters D-E-M-O-S trickle down the right side of the composition in separate discs; the discs hover above a naked man tied to a tree. Rauch’s paint handling is both tight and lose, detailed and cartoon-ish. Though Demos is teeming with imagery, I hesitate to delegate meaning for the very reasons provided by Volk: Demos is far too complex to pen in. Why shackle a dream?

Narrative structures rise and fall with ease before a Rauch or Stockholder alike. Though language becomes essential to how we interact with an art piece, it must be used with care. We rely heavily upon it, despite precariousness. It’s simply important the viewer recognize what’s been lost in translation. “In seeing, we typically substitute an appropriate language for the actual object in order to facilitate our ‘seeing’ of it – our language screens the object, it’s the grid that structures our perceiving.”(Art in Theory, p. 891) Mel Ramsden and Ian Burn (members of the Art & Language collective), specify ‘content’ as one ‘language’ of perception. When we attempt to interact with the piece, we are really interacting with the word, and also the concept of ‘content’. It perches on the edge of our thoughts, its gaze always piercing our analysis. Rather than interacting with the piece itself, we interact with an entirely different entity. What we define is ‘content’, content’s existence and content’s meaning. These findings are then related to other art pieces, and other forms of ‘content’. ‘Content’ itself can be broken down farther into various types and versions. Have we succeeded in our interaction with piece, as mediated by this concept?

Just as my right arm tenses and coils in preparation of its much- deserved ascent into a glorious fist pump of language-defying victory, muscles relax and straighten for mine is a false triumph. Whatever constrictive properties words may possess, my beloved representational images are likewise plagued. A non-verbal, two-dimensional depiction of a bowling-pin is equally at risk of absorption sans metaphorical mediation as its alphabetical counterpart. Bowling-pin has been visually identified, categorized and catalogued; we move on. In this way words and images run parallel rather than perpendicular; their function is similar. Both words and images are receptacles for meaning; these meanings are far less concrete than we’d like to acknowledge. Language is slippery; the concepts, truths behind its scrawl-y framework are more numerous than we’d like to concede. To fully access all that is found therein, we too must be lithe. This newfound fluidity may puff up or puncture depending on the angle of application. We are beings that enjoy systems, order and certainty. It is when those solid tenets of our reality are shifted that chaos ensues. It is imagination (and the ability to Not Panic) that negotiates this supposed divide between images, words and meaning (“knowledge beyond perception”).

The role of imagination cannot begin and end at a picture’s point of inception when freedom and possibility is the goal. For however high it feels I soar, buoyed by fantastical choice making, the ground is much closer than it appears. My wildest, wordless machinations must inevitably exist within the limitations of human experience. Though I may attempt to extend beyond my own perspective, the totality of such a measure is quite difficult to achieve. Even my temporary scapegoat for meaning (intuition) suffers a similar fate. How could we ever truly break free from our perceptions in pursuit “knowledge” and meaning? Here in Microsoft Office, knowledge itself if described this as “familiarity or understanding gained through experience or study.” Even if there were golden bushels of truth (and justification) to be plucked from temperate and untouched fields, with what hand could we employ for such a task? The successful achievement of utter possibility does not begin and end with me; I am disturbingly finite and far less wacky then I once thought.

This revelation is not an act of artistic deflation; it is a simple discovery of what it is to be of this world, to make work of this world and ultimately how said works can/will operate within this world. Stockholder’s aforementioned refrigerator is able to operate under many different guises beyond “refrigerator”. This ability is afforded “refrigerator” through words and imagination. Words provide the grid; imagination holds these words in check. “Refrigerator” can then move from “cold” to “withholding” with ease, while the object’s locus denotes domesticity. Though Stockholder does not claim allegiance to a single allegory by which the viewer must abide, she has most likely constructed a few of her own. In my own adamant refusal to verbally impinge upon the viewer-experience, I have denied myself the all too important opportunity to experience my work as a viewer. My freedoms have existed in action, not absorption.

The body of work to which this simple passage is found delicately stapled was executed as an effort to recognize and to harness the dual importance of artist and viewer in these flights of fancy (not sure I like this phrasing). While unfettered creativity is still essential, identification is no longer my foe. Counter to past concern, imaginative potential has not been compromised in this heady undertaking. A cycle between words and imagery was easily and organically established, between action and assessment. A number of numbered “thought-diagrams” were constructed in conjunction with two-dimensional “illustrative” compositions. Some diagrams precede their compositional counterparts, while others step in at the middle and end of production, respectively. At times the creamy off-colored squares resemble simple drills of word-association while others go a bit deeper. Semi-conscious observations otherwise ignored stand to be counted in sprouting bursts of verbal digressions. Their function is neither one of interchangeability nor one of opposition. They are imaginative investigations in their own right.

Drawings, diagrams and other incidentals combine to provide a visible progression; each advancing object/element is composed of preceding parts. These objects are not in the conclusion-business. Answers can stifle with premature arrival; inquisition is essential to discovery. It is inquiry that maintains a fluidity of thinking. It is not my wish to be dictatorial, but to foster. Though my curtains of creativity are pulled, and no thoroughly disappointing gentleman in a cravat and striped pants has been revealed, I still hesitate to assign meaning within this treatise. My drawings, diagrams and other incidentals combine to provide a visible progression. Each advancing object/element is composed of preceding parts and these objects are not in the conclusion-business. Answers can stifle with premature arrival; inquisition is essential to discovery. It is inquiry that maintains a fluidity of thinking. A dictator I am not, but a lone defender of imagination.

Yours and mine.

(Art need not be a drag, after all)

Bibliography

Westfall, Stephen. “Jessica Stockholder.” Bomb Magazine 41 Fall 2002: 92.

Volk, Gregory. “Neo Rauch: Time Straddler.” Art in America: International Review 6 June/July: 10, p.138-145.

Burn, Ian and Ramsden, Mel, “The Role of Language” in Art in Theory 1900-2000: An Anthology of Changing Idea (ed.) Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (Blackwell, 2002), 891-3.

Harrison, Charles, and Wood, Paul. Art in Theory: 1900-2000. Oxford: BlackwellPublishing, 2003.

Rauch, Neo. Tal, 1999. Private Collection.

Rauch, Neo. Demos. 2003. Private Collection.

Stockholder, Jessica. #291. 1997. University of Virginia: Art Museum.

“Play.” Art 2:1:Season 3. . PBS. 2005.

Random House Dictionary. New York: Random House, Inc 2010.

Friday, August 20, 2010

Technological Confused-ness--an essay

The average American experience is clamorous and image soaked, with mass production and digital media acting as the chief agents of saturation. In this newly digitized society, the screen has become a major player. Televisions jockey for ocular attention at bars as well as dentists’ offices while the Internet is readily available at any and all times (thanks to the Blackberry & its counterparts). Walking the streets of Center City Philadelphia, it is nearly impossible to meet the gaze of one’s fellow (wo)man, as most heads are tilted down in electronic concentration. How has this over-reliance on visual perception coupled with the digitization and multiplication of imagery affected our corporeal experience? It is my feeling that our relationship to the physical world as well as two-dimensional art has been greatly compromised in the sacrifice of the visceral to the LCD gods.

LG- Girl on the Left

RG- Girl on the Right

It is blush inducing to admit that it was only just one year ago that I came to this shocking state of awareness, horrifying in its simplicity. This discovery arrived in the form of a Renoir or, more specifically, his depiction of a dress. In the few moments before the museum closed, I stood basking in the blushing cheeks of Two Girls. They are seated in chairs set outside, in what appears to be a field. Because the composition is cropped fairly close around them it is hard to officially discern what sort of activity engages them. The girl on the left (LG) is looking straight out in front of her. Most of her back is to us though the composition is angled as such that we can see a portion of her left side as well as her cheek and the curve of her eyelashes. The girl on the right (RG) is turned toward LG; as a result her face is also turned outward toward us though her vision is not directed at us. She is dressed in a bluish black while her companion is more lightly attired in a yellowish-pink pastel. RG’s eyes are deep, wet violet and she looks somewhat forlorn; there’s a weight on those smallish shoulders. Why so sad? The day is bright and the two girls are seem to be caught in an act of leisure, though their mode of dress is a bit constricting and formal.

Up to this point, my attention as a viewer had been directed exclusively towards the second dimension until a small three-dimensional “fold” in LG’s dress pulled me out into my own fleshy reality as well as Renoir’s. One small swab danced out from the composition to declare “Hey! I’m paint!” In that instant the dual reality of Two Girls’ existence became abundantly clear. This painting exists as both representation and object. Through Two Girls we are exposed to three moments/cycles of time:

1. A sunny day, if not multiple days, in a field with two fresh faced girls.

2. A year’s worth of physical labor on the behalf of Renoir, which may or may not have occurred on site, in the field.

3. The painting’s existence from completion to the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

All of these lifecycles carry informational tools essential to the enrichment of artistic and humanistic experience. In this object we are given access to many hands and lives, but only if we are able to perceive it as just that: a physical object. Though Two Girls is plenty beautiful and interesting, we lose much by regarding it as composition alone.

As a painter, it feels as though my world has been rocked, my artistic reality shifted by the revelation of a simple card trick. His handling of the paint speaks to both a love of the act of painting as well as tenderness towards his subjects. The flowers atop LG’s hat burst as the fold of her dress does. There is an excitement about the application of pigment to which I can surely relate. Renoir and I share a love for the action. However, these formal flourishes do not detract from Two Girls’ representational function. LG and RG are not beside the point. As painting is an activity I likewise relish, I am quite familiar with that gray area between action and representation. How could it be that the sheer magnitude of this gray area (between image and object) has only recently emerged in my conscious?

As earlier stated, I believe digitization, mass production, multiplication and screens have all played alternate roles of importance in this sensory imbalance and confusion. While rummaging around on the third floor of my apartment, I found a stack of my housemate’s photographs. The images elicit memories spanning from adolescence on up to adulthood, middle school to college. Hair went from brunette to blonde back to brunette while noses were pieced and plain once more. The photo’s themselves were caked in plaster, an obvious result of being stored with art supplies.

Though a photograph is a flat representational window, it is the product of a number of physical reactions and processes. A button is pressed on a cool autumn day, light hits gelatin and burns an imprint onto a strip of film. The roll is then brought to one’s standard photo-mat of choice in order to be processed, perhaps by a tired teenager, only to be excitedly reclaimed days later. The photos themselves then travel from place to place, apartment to apartment, shoebox to shoebox. That photo has a history and life beyond the one it documents. At this point in time, digital photography has almost fully replaced film-based photography in recreational usage. Whole albums have come to exist completely on the computer, in virtual folders and assemblages. They are easily posted online, to be tagged and accessed by others thanks to social networking sites. The Internet is flush with personal imagery. In this format, it is more and more difficult to discern the difference between one photograph and the next. If you’ve seen one girl in a fedora vamping for the camera, it feels as though you’ve seen them all.

Mass production and multiplicity throw individuality and specificity right out the window. Yes, the girl with the fedora is a particular girl in a particular fedora. Perhaps she cries at sad movies and is allergic to strawberries. Perhaps her fedora is soft and velvety. Perhaps it was her father’s and that’s why she wears it. Mass production of both objects and imagery washes those particulars clean in such a way that we cease to wonder what they are and where they went. Human hands are seemingly removed from our objects. A chair from Ikea may seem quite neutral, free from human touch; it is actually the product of numerous human-made systems. From design (conception) to delivery, that chair passes through many human hands and minds. However, automation wipes these crucial individuals clear from our minds.

For a potter produces his forms by placing his hands and fingers in particular positions to make clay shapes. And when we are able to find these positions with our own fingers a pot can spring to life in an extraordinary fashion. With more standardized and repetitive ceramics these positions may be rather stereotyped; with mechanization they don’t exist at all. (Rawson, 20)

The generic make-up of an Ikea chair likewise prevents us from making a specific relationship with it. You’ve sat in one you’ve sat in them all.

Finally, computers and the Internet combine to create a rift between our consciousness and our bodies. Like a disembodied eye, we go forth and ferret. Though hands are crucial in the act of surfing great swells of information they swing on mechanically, as an afterthought. Chairs hold aching buttocks, backs curl in a rictus-producing hunch while minds expand under the expanse of overabundant KNOWLEDGE. Corporeal existence is almost forgotten in this act of acquirement. “Car-bodies, stainless steel gadgetry and especially television images all conspire, by a sort of sensuous castration to destroy for us the whole realm of touch experience.” (Rawson, 19/20) I believe Philip Rawson’s statement is easily applied to the computer. It is there that I may travel to Hawaii without ever having to, as if the computer could fully translate that experience.

It is not that the procurement of online information is completely evil; it is both beautiful and wondrous how many doors the Internet has been able to open. Access to knowledge has always been a class issue and the Internet has the power to level the playing field. That being said, it is worth analyzing its affect on sensory perception. It is also worth pointing out that for every nugget of genius, the Internet has 10 nuggets of garbage. The garbage combined with the “need for speed” and immediacy in this cultural moment does not foster intelligence. What it does foster is the concept that a little bit of information is enough. As with the Hawaii example, for all the digital images (both mobile and static) I’ve seen in my life, I do gain a vague sense of familiarity that masquerades as concrete experience. A friend told me recently that he loves, Loves Kandinsky but had recently realized he’d never seen one of his favorite paintings in person. When he was finally given the chance, he felt a disappointed air of ruination and he got grumpy. He left the museum disillusioned.

As this friend of mine just so happens to be a bit of a curmudgeon, I can’t help but feeling that had he spent a bit more time with the actual Kandinsky, something may have come forward, an element misplaced in multiplication and reproduction. Or maybe whatever Kandinsky had to offer my friend did not exist in the physical realm at all. It is possible that in this case the painting had little to offer that particular fellow in that particular moment. I would argue that since the object begs a consideration of physical process and production, a live-read has much to offer. It’s simply up to the viewer to enter into a dialog with the object as object. Though Rawson focuses his attention upon three-dimensional objects, I don’t think his points have to be limited to them. Touch is very much a part of looking at a Renoir. Apparent brush marks bring his arm back to life, alive in the mind of the viewer. This affect is not easily achieved via Google images.

I do not blame digital media as the sole dictator, holding court over my senses and my artistic consciousness. If I want to know something, but go no further than Wikipedia or the first website I find, the Internet is not to blame but myself. The choice is up to me. I must decide how far I wish to go in order to gather the richness of artistic experience. However, I do think it [digital media] has had a robotic hand in my development, not fully realized until a warm summer afternoon in a quiet museum.

Bibliography:

Rawson, Philip. Ceramics. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press, 1984. Copy.

Teresa Palmer review--the windy version

As MFA students, we ferret and forage. Tromping in great clusters through gallery and museum alike, we hungrily search for meaning, beauty and sublime transcendence, damn it! In this way, it is easy to overlook the richness to be had on our own front porch; we are so fervent in our exploration. Quietly hanging on the north wall of Rosenwald-Wolf, a mysteriously untitled painting awaits its much-deserved glory. It shall wait no more.

The title card simply reads “Teresa Palmer, Third Year.” This nameless painting is just one part of This is Complicated, a fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants curatorial endeavor at the University of the Arts. Purportedly, pieces were chosen on a Wednesday, installed on a Thursday, and surrounded by wine, cheese and judgment on a Friday.

For all its spontaneity, the show has served one important purpose: to bring graduate art out of the private quarters of the artists’ studio into the world, prime for public consumption. And consume I have. Palmer’s surfaces are luxuriant; they drip with sumptuous glazes and pigments. Her handle on color is breathtaking, whispers of orange interplay with great swathes of viridian. Not a single pigment has been muddied in Palmer’s practice; her grays are the product of careful consideration. Though Nameless* could exist as a purely formal feast for the color hungry eye, there is much more to the work than simple ocular penny-candy.

Within Nameless’ borders, a strange present has been created. Palmer’s painted world breathes. Though her chosen pockets of definition are still somewhat ambiguous, color generates a potent tenor. The sky feels threatening; dark trees are silhouetted against its tranquil purplish-menace. Two female figures exist in the foreground, positioned in front of a greenish architectural space. The space is open and well lit. The angling of the structure is almost reminiscent of Hopper’s Nighthawks’, though the tenor is quite disparate.

The figure on the left (LF) stands, while the figure on the right (RF) appears to be seated. LF’s face is a space of modulating, flat warm grays. On the right edge of this facial field lay a few careful swathes of brownish pink. Palmer’s delicacy has allowed these marks to exist both as “face” and “mark”, representation and abstraction. The woman stands with weight but is also somewhat form-less. Her knee is a burst of orange red that almost fades into a warm gray field making up the floor.

While LF is turned at a sort of three-quarter profile (she looks out toward the right), RF looks outward and down. Her body is curled and turned toward the second figure. RF’s pallor is composed of pinks and purples rather than the warm grays and oranges of her counterpart. One of her arms is bent out and around, as if she is holding something; a swirl of brown is met by chunks of pink and white. Her face is somewhat more defined but her eyes are warm, dark holes. The little definition Palmer has included creates an air of uncertainty and pain about RF.

After a long close inspection, Nameless feels both definite and dubious. Forms are found through scrapes and drags; from chaos this semi-serene nocturnal-space finds structure. A strange and ambiguous narrative exists somewhere between Nameless’ borders. Palmer’s pockets of definition seem purposeful, but by no means controlling, points of departure. The power of interpretation seems to have been firmly bestowed upon the viewer. LF stands as if attention, ready for orders while RF shrinks and shrugs into a loose ball. She too acts as a receptacle for meaning.

At first visual stab, the full weight of this dominion feels slightly uncomfortable. Confusion is not a fair exchange for pedantry. However, after all intellectual performance anxieties have calmly subsided, Nameless is given a chance to fully appear. This manifestation of meaning is in no way static. Just as you feel as though you have a handle on the piece, something changes and falls away. RF and LF are fleshy ghosts; they are both inhabitants of space and wandering wraiths without residence. There is very little interpersonal or environmental communication. Though RF sits, her interaction with the entire space is minimal. What is created is potent atmosphere of isolation and physical alienation, not unfamiliar terrain in this digitized age of mechanization.

Where does Palmer stand in this psycho-emotional haze? Perhaps Palmer is commenting on the weakness oft assigned the female sex. One could draw meaning from the neutrality of LF’s color structure played against RF’s more traditionally feminine coloration. She, the more feminine female figure, seems feeble compared to the strength of LF’s stance. LF’s hair is back while RF’s hangs down about her bare shoulders. Cultural mores and rules regarding femininity frequently involve hair. The figures exist in a seemingly domestic space. Domestic space, in turn, reads as feminine space, though the sharp angularity of the structure could be construed as strictly masculine according to a system of stereotypical gender binaries.

These inferences of signification, while interesting, do not come any closer to an effective solidification of Nameless’ contents and meaning. In this case especially, a concerted effort to substantiate intentionality would be an exercise in self-limitation. To simply dissect and classify Nameless’ more definite parts is not the best way to get at this work’s meaning, as there are many meanings and experiences to be plumbed from Palmer’s painterly depths. Nameless’ refusal to be pinned down, between materiality and meaning, specificity and ambiguity, makes for a rich viewing experience, one that demands re-visitation.

And that’s a good thing.

***Go, see the painting and if you still don’t agree—I’ll eat my hat. Tell ‘em Jessie sent you***

Friday, May 7, 2010

Kierkegaard--theory extended

Kierkegaard’s structure for tensed time is fully derived from the “lives of the selves” (Taylor, 318). It is born from the temporal interplay of man as object (matter) and man as subject (consciousness). One is finite and limited while the other feels limitless by way of imagination. Taylor begins his breakdown of Kierkegaard’s theory with a passage from A Concept of Dread. The passage reads as a series of equations (if a=b=c, than a=c and the like). In the interest of clarity, I’ve decided to break the passage down into a simple list:

1. man is spirit

2. spirit is self

3. self is the relation

3a. this relation is one that relates itself to itself

4. man is synthesis

5. synthesis is the relation of two factors through a third

6. the four factor pairings synthesized by man are a) infinitude/finitude b) soul/body c) possibility/necessity (actuality) d) temporal/eternal

7. self is the third factor bringing all four factor pairings together

(Kierkegaard, 315/Taylor 318-9)

Taylor then provides two caveats posited by Kierkegaard to this synthesis of man. The first caveat arises through the soul-body pairing. “The synthesis of the soulish to the bodily is to be posited by the spirit, but the spirit is the eternal” (Kierkegaard, 360-1/Taylor, 319) If the self is spirit and the spirit is eternal, then the self cannot synthesize temporality and eternality; the self is equivalent to one of these factors through the spirit.

Kierkegaard’s second caveat is this:

The self is composed of infinity and finiteness. But the synthesis is a relationship which, though it is derived, relates itself to itself, which means freedom. The self is freedom. But freedom is the dialectical element in terms of possibility and necessity

(Kierkegaard, 162/Taylor, 321)

Taylor explains the second caveat (self = freedom) this way: man is self and self is freedom. That (wo)man is the synthesis of the finite/infinite as well as possibility/actuality refers to his/her “historical situation and [his/her freedom] to act within the limits of that situation” (Taylor, 322). One’s finitude speaks to the concrete trappings of one’s situation, a place “from which the self must proceed” (Taylor, 322). “Infinitude” is, in part, the “capacity of the individual (historically situated) to imagine alternate courses of action” (Taylor, 322). It is his/her ability “to entertain different possibilities” (Taylor, 322). The actuality of one’s “historical position,” will affect the amount of seemingly infinite possibilities a creature of finitude is able to comprehend.

This passage speaks to the problem of enslavement. How can the self be freedom when one is in bondage? Since imagination is a key factor in regard to the “entertainment of possibility” and imaginative thinking, this will most likely vary from person to person depending on their “finite” or “historical” condition, their actuality. Imagination is a place where the real and ideal meet up. It is “by means if imagination that an individual can envision different possibilities which can be enacted…Here he can distinguish between his possible self and his actual self.” (Taylor, 322).

Paper....DONE!!!-->kierkegaard and painting and you

Start of paper:

In a darkened sky punctuated by illuminated tufts of clouds, the hazily obstructed light of the moon softly grazes a single sail. Extending from the mast of a lonely seafaring vessel, the resilient cloth is taught and wind-filled. It is curved dutifully in a course presumably set towards the other side of a rocky bluff. Two figures emerge from the shadows a few hundred feet up the beach, just left of where I stand. The same soft lunar light smoothes a yellowish landing strip stretching hazily from the frothy waterfront right up to the tips of my toes. However, were I to feel the sharp and grainy squish of sand between my toes at this particular moment, I’d be much disturbed. It is linoleum upon which my rubber-soled feet (squeakily) rest and pristine walls surround me, not a blanket of stars. This ghostly beachfront does not extend beyond its angular gilt captor.

How is the viewer to reconcile his/her temporal experience of that which occurs betwixt ridiculously ornate frames with the reality beyond fancy rectangles (white walls, hushed tones) all within a single moment: a single confused “present”? Such is a confusion oft produced by simultaneity.

RS: Rocky Seashore

ST: Spatialized Time

LT: Life-Time

Since this beachfront scene (Rocky Seashore) is naught but a succession of marks laid upon taught canvas in 1876 by a fellow named Ivan Konstantinovitsch, shouldn’t the guard telling my boyfriend to shut off his cellphone be more “present”, “real” and “now”? Can the two presents be equal when one is obviously past? This line of questioning is limited by its linearity, it employs what Soren Kierkegaard called a “spatialized”* understanding of time: a sort of temporal understanding and measurement he found much lacking. In its stead, Kierkegaard has provided a more self-centric understanding of time (“life-time”), a solution to this problematic Aristotlean construct. It is this theory of tensed time and measurement that has much to offer the average museum-attendee; the application of which is a definite act of expansion.

Before moving forward with an explanation and application of Kierkegaard’s theory, it is essential that I provide a couple of clarifications. Firstly, much of my own understanding of both “spatialized time” and “life-time” is firmly entrenched in Mark C. Taylor’s “Time’s Struggle with Space: Kierkegaard’s Understanding of Temporality.” This work has proved to be a crucial reference point. Though Taylor’s article is thick with direct passages from both Aristotle and Kierkegaard, the level of understanding I have achieved has undoubtedly been influenced by Taylor. Though I will continue to refer to Aristotle and Kierkegaard directly, the reader should be forewarned of Taylor’s indispensable role. As my intention is not to prove or disprove Kierkegaard’s theory, this divulgence should not prove utterly devastating. Secondly, if “Aristotle’s discussion of time [has] remained decisive” (Taylor, 312), why should Kierkegaard’s LT prove more pertinent to my analytic endeavors? Aristotle’s name is well marked in the annals of time (capped with an “A”, set atop a well-smoothed marble pedestal). I’d imagine his theories have survived for a reason. What could Kierkegaard possibly have found insufficient in Aristotle’s version of temporality?

ST is the measurement of an object’s movement through space. These movements can be viewed as a progression of points along a single line. The line of time (upon which the object moves) is composed of an “infinite number of points,” each point acts as a “successive present[s] differentiating past from future”(Taylor, 315). There is no overlap between the tenses of time, the “boundaries remain well defined” (Taylor, 315). According to Taylor, one of Kierkegaard’s primary difficulties with Aristotle’s theory is that it does not allow for human perception and consciousness. ST is applied “universally and irrespective of…character” (Taylor, 315). A human, a bar of soap, and a painting are all treated identically. However, a bar of soap has no awareness of time whereas a human most certainly does. Within human perception, the past and future can exist (in some form) in a simultaneous moment of “present”/”now”. Taylor has included a passage from St. Augustine’s Confessions, which seconds Kierkegaard’s emotion.

All this I do in the huge court of my memory…I can take out pictures [mental] of things which have either happened to me or are believed on the basis of experience; I can myself weave them into the context of the past, and from them I can infer future actions, events, hopes, and then I can contemplate all these things as though they were in the present.

(Augustine, 218-9/ Taylor, 312)

The boundaries of Aristotle’s point based system are created by the spatialization and visualization of time. One cannot exist at two points at once just as one cannot exist in two places at the same time. With consciousness, overlap does occur. Perhaps Aristotle’s line of time would work more swimmingly in a world unconscious to time, because it is in awareness of ‘present’ that the problems of linearity occur. “As far as the non-human world is concerned, time remains a perpetual flux in which there is no differentiation between past present and future”(Taylor, 329). Tensed time “emerges only in connection to man’s purposeful activity”(Taylor, 329). The concept being offered here is that, though Aristotle’s theory does function, time measurement is a human tool and it would do well to allow for the inner workings human consciousness. What need has a panther for Aristotle, however objective his stance?

Though a painting is a conscious-less object, it is the projection of consciousness. A painting is perception made manifest, put forth to be perceived. The object itself is a conflation of multiple points of time into an objectified whole. Multiple hours of “studio-time,” sittings and whatnot, are condensed and received as one. Post-completion, it moves from wall to wall, from cozy and private to stark, cold and public. The object then moves through minds. There is no allotting for this experience with ST. It is because the art object is so linked to human perception that Kierkegaard’s LT is far more applicable to the temporal experience of art.

Kierkegaard’s structure for tensed time is fully derived from the “lives of the selves” (Taylor, 318). It is born from the temporal interplay of man as object (matter) and man as subject (consciousness). One is finite and limited while the other feels limitless by way of imagination. Selfhood is not a simplistic entity; it is an intricate system (Taylor, 319); a vessel of duality. Within the self, the finite is put in relation to the infinite, as is possibility and actuality. Selfhood creates the relationship; the pairing is a synthesis.

Finitude of self is comprised of the concrete elements that compose one’s situation; it is the place “from which the self must proceed” (Taylor, 322). Meanwhile infinitude of self is, in part, the “capacity of the individual (historically situated) to imagine alternate courses of action” (Taylor, 322). It is his/her ability “to entertain different possibilities” (Taylor, 322). Actuality and possibility are essential to a human comprehension of the finite and the infinite. The actuality of one’s “historical position,” will affect the amount of seemingly infinite possibilities a creature of finitude is able to comprehend. The self is free, but only so free as one’s position allows.

This system of self and synthesis has close ties with the construction of (measured) time. Temporality is put in relation to its twin (eternity) within the “self system”, though it is not the self that synthesizes these factors. According to Kierkegaard these dual elements are mated and processed inside of “Oieblikket”. Unfortunately much is lost in translation (as Taylor is so good to acknowledge); this can have a grave effect upon writings of a philosophical nature. That being said, the Danish word “Oieblikket” loosely translates to “the moment” or “the instant”. A concept of the “present” is a mixture of these two syntheses: self and Oieblikket; it is the inter-play of the possible and the actual inside an instant. To put it simplistically, the present “is the moment of decision” (Taylor, 324). Here the past and the future touch, overlapping ever so slightly through thought on the verge of action. If the actuality of self is established through one’s past sufferings and actions while possibility exists as a future not yet realized, human consciousness can allow the tenses of time to exist in partial simultaneity through decision. There is no clear dividing line between past and future. Taylor proceeds to insert three more consciousness-based terms into the pre-existing tenses of time; past, present and future become remembrance, decision, and expectation. All three are actions that can be executed in the present tense.

So here I am back at The Rocky Seashore, to experience this pictographic present for a second time. In this two-dimensional Oieblikket, the moonlit strip reaches for my toes once more. How does Kierkegaard’s LT apply to my experience of RS? We know that within a theory of ST, the representational contents of RS could be distinguished as a past that had ceased-to-be. An experience of RS’s still waters must be somewhat unattainable in my present (due to its non-existence). ST defines the past as something that is no longer there to be referenced; it cannot exist in simultaneity with the present. In defiance of Aristotle I (my body) stand(s) in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, while my mind is on the beach. It swirls murkily through a blended cloud of actuality and possibility, engrossed in the instantaneous cycle of decision. Isn’t this present, this Oieblikket, a bit more illusory than the average “moment of decision”(Taylor, 325). Though it feels as though the boat may continue on its course toward the rocky precipice, I know it cannot. Two shadowy figures hold me in their gaze. What questions might they have for me as we meet further down the beach? None, because such a meeting cannot and will never occur.

If the present moment is one of decision, what can I decide that will translate to actualization regarding the contents of this painting? There is nothing I can do to physically change this painting (on the right side of the law). Anything I can and would do on the wrong side would only shatter the illusion of a dual-present. I’d need the artist’s hand to further the boat along its course: a hand that is long since deceased. It is ultimately through imagination that my application of LT is made both fitting and appropriate.

We will now think of a youth. With his imagination he constructs one or another picture (ideal) of perfection, whether it be one handed down by history, that is, belonging to a time past, so that it has been actually, has possessed actuality of being, or whether it be formed by imagination alone, so that it has no relation to the time or place and receives no definition by them, but has the actuality of thought. (Kierkegaard, 185/Taylor, 323)

Though the picture to which Kierkegaard refers to an idyllic youthful creation of self, an imaginative essence far more changing and changeable than a painting on a museum wall (physically speaking), it is on the quality of imagination I’d like to focus. Though Kierkegaard describes imagination as “endless remoteness from actuality,” (Taylor, 323), it seems as though it can achieve “actuality of thought.” The latter picture (based on imagination) is termed as having this sort of thought-based actuality.

I would suppose thought-based actuality could be accompanied by similarly imagined possibilities. However, James Elkins, Professor of Art History at the University of Chicago, may beg to differ. “Painting is an art based on inherently motionless figures, which are very different from frozen figures that are captured by the camera…I cannot imagine a painted figure moving or talking unless I am willing to settle for comic travesty…If I am more serious about painting, I have to acknowledge that motion is not just absent but inconceivable” (Elkins, 220-1). What Elkins has pointed out makes sense in literal manner; if I were to conjure the sight of the boat moving across the water the result would, in fact, be cartoon-ish. However, I have the ability to stave off a complete visualization of the boat’s possibilities. Though imagination is the means by which “an individual can envision different possibilities” (Taylor, 322), the execution need not be sight-based. The existence of the art object within the mind of the viewer is somewhat separate from its physical presence. Its imaginative presence (within the viewer) is an actualization of thought. It is mostly up to the viewer what possibilities are allowed to affect this picture. This is a part of the process of “deciding” (in viewership).

In many ways an art object has two cycles of “life-time.” These cycles exist through different selves: the artist-self and the viewer-self. The life-time within the artist’s self system is one of physical actualization. Each brush stroke is a moment of decision made physical/actual. Though an artist may work from a sketch or a plan, deviation and/or adaptation often occurs. Colors may react differently than originally anticipated, creating an effect outside of intention. In such a case, the artist must change the route of execution, or risk changing the entire result. Even when choices are seemingly made in advance, there is room for decision and change. The artist steps back and, in this moment of completion, the painting is released into its second life-time within the viewer.

Some paintings are better at engaging the viewer in a more active present (Kierkegaard’s present of decision) than others. Compositional tricks such as perspective and an outward looking gaze can do much to actively involve the viewer, to make the viewer feel as though s/he is an active participant. In the case of Konstantinovitsch’s Rocky Seashore, it is both perspective and atmosphere that give me a feeling of present/presence within the frame. The aforementioned strip of moonlight plays upon the beach; its brightest beach- front point echoes the enveloped moon and stretches right out to my bodily position. Despite its limitations (in actuality the “moonlight” is only able to reach the bottom of the canvas), my physicality has successfully been activated. The two figures seem to turn towards me. Shadowy as they may be, it is not a far leap to feel acknowledgement in their affectation. Here, though it is a figment of my imagination, it is as if the painting has engaged my actuality in its air of possibility. The possibilities held in the atmosphere of RS’s darkened sky resonate with those I’ve felt under similar skies. The particular deep purplish-blue of the night sky punctuated softly with the muted and cloud-gauzed moon is of the kind that can fill the chest with the magical potentiality of life. This is the sort of night charged with happening. In the busy-ness of day as well as the business of city life, it is easy to feel caught and constrained by routine, no longer cognizant of freedom and potential (decision). Under such a quiet sky, however, all is silent, clear and possible.

This dual Oieblikket between RS’s painted contents and my own bodily organism engages both of our actualities. The actuality of RS as representation is very-well set. Whatever could or would occur to change RS would only work to change it as an object, not an image-based narrative. Smashing, damage and discoloration all affect the object as a whole. The narrative would, in many ways, remain unscathed. The other actuality engaged is my own, by way of my past. That which is necessary is “given to the self” (Taylor, 322). It is the point from which the “self must proceed” (Taylor, 322). My actuality (past and necessity) and the physical actuality of RS as a completed artwork are dual precipices, towering over the possible in conjunction with one another. My actuality, my past contributes to the possibility held in such a sky (however unchanging); it is a possibility held within and actualized by my imagination.

DFTP: Departing for the Promenade (Will You Go Out with Me Fido?), Alfred-Émile-Léopold Stevens, 1859

The outward-looking gaze is another potent tool elicited in the engagement of the viewer. Would the Mona Lisa have ascended to such notoriety without eye contact? In Departing for the Promenade (Will You Go Out with me Fido?), the visual hook of two-dimensional eye contact is a flourish, an aside; though it would have been no more effective at capturing my attention had it been a central focal point. A young woman, fully clad in a mode of dress befitting none other than Vivian Leigh/Scarlet O’Hara (but perhaps a tad more modest), is the central (human) figure in DFTP. Groupings of long cylindrical curls fall out of her open bonnet. Her chest is fully turned toward the door, while her face angles over her right shoulder. Her right arm is extended; its right hand holds the door handle. The doorway is not quite parallel to the rightmost vertical edge of the canvas; the wall-line recedes diagonally inward from the bottom-right corner. Behind the young woman, the doorframe meets a sidewall edged with a well-upholstered couch. Over the couch, hangs a portrait holding a grey-wigged woman inside its borders. As the woman steps toward the door, the glance thrown over her shoulder tips down toward a small, poof-y white dog. The dog’s gaze is pointed upward in turn, towards the woman, and you can tell by its gate that it is quite excited. This canine-human rapport is buoyed by the playful parenthetical addition to the main title of DFTP (“Will You Go Out with Me Fido?”).

My first impulse, due to the painting’s fine execution, is to engage the piece as an artist in admiration of another’s craft. While breathtakingly executed, the dramatic atmosphere of RS couldn’t help but expedite sensorial experience well ahead of a colder craft-based appreciation of the work. DFTP, however, had me at “cufflink”. The doorknob bound hand is lovely, but the white cuff encircling it is lovelier. It is pinned by a single golden button that sings: a single point of delightful reflection that fills me with envy. I will never paint such a cufflink; it’s just not feasible. Each wooden “V” of the floorboards seems perfect, straight and efficient. Upon closer inspection, the sienna hue of the flooring thins out on the left side of the composition (revealing the surface of the panel as well as the artist’s hand). This chink in the painting’s seamless armor only works to further connect me to the craftsmanship of the work: the painting’s first cycle of life-time. It is the be-wigged vestige above the extravagant couch that pulls me into the moment, the narrative-Oieblikket.

Here in “the instant” my wandering eyes meet those of this woman, gazing out from her own golden frame (a rectangle within a rectangle), and I feel as though I’ve been caught. Until now, I’d been able to peruse as I wished, unencumbered and unnoticed. Such freedom could not continue under this doubly framed gaze. The spectacles of professionalism are knocked from my unsuspecting brow, all by an inanimate and be-wigged duchess-of-so-and-so. My eyes return to her over and over again, each time in reception of recognition. In this one quiet detail (an afterthought perhaps) I am brought into this two-dimensional world anew. However, it is not in totality I enter. I feel like a ghost, a spectral presence spotted by a sister specter. Perhaps she stares from her own portal, a portal where it is she who is flesh and I that is artistically rendered. Of course I do not believe this to be possible but imagination brings potential no matter how false.

Even with the power of imagination at my disposal, I remain on the periphery. The little white pup’s attention remains eternally clasped upon the exiting woman. She returns it in kind.

MF: My Friends, Viggo Johansen, 1887

Viggo Johansen’s My Friends takes my perceived marginality one step farther. My experience of MF is Scrooge-like in quality, only in this case I have visited the Christmas Past of another. Blushing faces, aglow in the light provided by a single gas-lamp, circle round a table in festive conversation. A smile plays on a handsome blond woman’s face; her blue eyes are edged and lightly creased with warmth. Two male figures stand to the right (our right) of the table, barely visible in the outskirts of the dim room. Though the room is dark and intimate, I do not feel inclusion. These are not my friends; with nowhere to place myself I am barred from the occasion. Such an impression may simply be the bi-product of my own propensity for social awkwardness (I’m shy!). As I am only able approach the painting from my “historical position” and my base of experience, this initial sensation of distance cannot be helped. I am left on the threshold to observe, not participate. As Scrooge, I move unseen, unheard, and unable to act upon this merry scene. Just as there is nothing he can say or do to affect Christmas’ Past, I feel similarly ineffectual.

Perhaps the viewer is powerless; the narrative is the past tense, having already been decided. S/he may see traces of a passed present by way of a brush-mark, evidence of the artist’s once-lively hand. As the mark represents a decision made, a potential actualized, the viewer is perpetually off by just one moment. Two-dimensional narratives will remain perpetually on the verge of progression, to no avail. To this argument I’d offer a similar experiential comparison, to that of the theatre. In theatre, the audience has no control over the narrative; the narrative cannot be changed. An audience can affect a performance, but to do so would only break the illusion between story and stage. The players are affected but the characters remain intact.

Theatre is an art that continually challenges the idea of the “present”. Actors, in their best moments, are able to experience and project scripted and predefined moments as if for the first time, in defiance of reality and tensed time. Because the play is written, read and practiced, the most gifted actors are able to make a moment of remembrance one of decision and possibility. The audience knows all has been decided and can know what has been decided in advance. They too have the power to defy time and hope where there is none. Macbeth will forever kill the king; Romeo and Juliet will never live happily ever after. That we enter into any play with any modicum of hope is a triumph of imagination.

Theatre as a time-based medium allows for a more seamless experience of “present tense” (the moment of decision) in narrative, while suspension of disbelief and imagination fills in any gaps. Such a suspension is slightly more difficult when approaching an object fully formed; there is a great difference between the act of reading a script and that of watching it performed. If theatre audiences as well movie audiences settle in all the same, for a story felt and projected in real time, why can’t the museum attendee? The power of decision, though limited to imagination, can bestow a great gift upon the viewer. Even its limitation can provide the viewer with a far richer relationship to art. Though there are gaps in its relevant application, Kierkegaard ‘s “life-time” (as imparted by Taylor) has most definitely expanded upon my concept viewing as a temporal act.

Why not spend an afternoon in transcendence of linear time…at the museum? It’s up to you.

Bibliography:

Elkins, James. The Object Stares Back. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996.

Taylor, Mark C. “Time’s Struggle with Space: Kierkegaard’s Understanding of Temporality.” The Harvard Theological Review 66.3 (July, 1993): 311-329. Jstor. Web. 14 April 2010.

Hardie, R.P. and Gay, R.K., trans. The Works of Aristotle Translated into English. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1970.

Augustine and Warner, Rex, trans. Confessions. New York: Mentor-Omega Books, 1963.

Kierkegaard, Soren and Lowrie, Walter, trans. The Concept of Dread. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957.

Links to images (experienced in person):

Konstantinovitsch, Ivan. Rocky Seashore. 1876. Painting. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia. Philamuseum.org. Web. 29 Apr. 2010.

http://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/102719.html

Johansen, Viggo. My Friends. 1887. Painting. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia. Philamuseum.org. Web. 29 Apr. 2010.

http://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/101698.html

Stevens, Alfred-Emile-Leopold. Departing for the Promenade (Will You Go Out with Me, Fido?). 1856. Painting. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia. Philamuseum.org. Web. 29 Apr. 2010.

http://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/104330.html

Friday, April 2, 2010

FINAL FINAL, w/ out italics and bolds--sorry, the cut & paste doesn't translate.

Perception and Understanding in the Post-Post Modern Age:

A prologue:

Random House American Dictionary (Pocket Edition)

perceive: 1. gain the knowledge of by hearing, seeing, etc. 2. understand

perceptive: 1. keen 2. showing perception

understand: 1. know the meaning of 2. accept as part of an agreement 3. sympathize

understood: agreed or assumed

sympathy: 1. agreement in feeling, accord 2. compassion

empathy: sensitive awareness of other’s feelings

interpret: 1. explain 2. construe 3. translate

agree: 1. consent or promise 2. be in harmony 3. be similar 4. be pleasing—a. agreement

subjective: 1. personal 2. existing in mind

Perception is a multi-tiered, multi-faceted and downright complicated action. It would seem the act of human perception lies somewhere between mind (subjective interpretation) and matter (pure sensory experience.) However, no clear line of demarcation exists between these two realms. Random House Dictionary splits the verb “to perceive” into two parts:

1. gain knowledge by hearing, seeing, etc.

2. understand.

The word subjective is likewise doubly divided:

1. personal

2. existing in mind

As we are incapable of “existing” outside of the “mind,” what we perceive can’t help but be warped. Its luminescent rays of understanding are forever tugged into subjectivity’s hole-y void.

…all organisms actually live in duree reelle, or real time, in which waiting for a teapot to boil may seem an eternity. In any case, change is observed change, and in spite of strenuous efforts, no one has ever proved out a totally neutral, purely objective standard of observation. Perception is an essential aspect of reality. When we perceive a different world, the world becomes literally different. (Leonard 120/1)

The same Random House Dictionary divides the verb “understand” into three parts:

1. know the meaning of

2. accept as part of an agreement

3. sympathize

If perception is both an “essential aspect of reality,” and completely fluid, how do we resolve the “agreement” aspect of understanding as it would seem it is at risk of opposition to the subjective nature of perception. What happens to understanding when our perceptions fall out of line?

**end prologue**

A work of art provides an experience and it is an experience in delay. The artist creates a work at one moment in time (many moments in actuality) to be experienced in another. As it is shared, be it by museum wall or some other venue, the viewer experience resides in their temporal and perceptual reality. When an art piece strikes a chord, that chord reverberates within the organ of the viewer. It resonates within that viewer, vibrating off their perceptions, experiences, memories, and knowledge. As an artist, I hope to be understood and as a viewer, I hope to understand. These goals seem quite lofty and unattainable in the face of subjectivity. If my “organs” are composed of my perceptions, can the harmonious chord of understanding truly be struck if my knowledge and experiences are insufficient or disjointed? There is no way for me to tap Van Gogh upon his thin and bony shoulder to simply ask him if I got it/him “right” (and then maybe give him a sandwich or a hug.) Art creates an intimacy between viewer and artist, but this intimacy can feel cold and questionable in comparison to experiences shared in real time. When I make my mother laugh and our eyes meet mid-roll during a particularly bad episode of insert bad medical drama here: that sort of mutuality is potent and seemingly stable. All feels right with the world in that perceived moment of knowing and being known.

Humans (among other creatures) value stability and order; we long to have a “world” or “reality” that adheres to these values. Once the established “rules” are intact (however shaky they may be in actuality) a disruption of said rules is not entirely welcome. To achieve a true state of understanding, both knowledge and acceptance (if not agreement) are necessary. When disagreement arises, this stability is compromised. Though it’s become a fairly well known adage within U.S. borders that different folks require different strokes, the phrase often meets with contention in execution. Acceptance and agreement are so closely linked that participants can’t help but be changed in their process of establishment. If one fears the change, resistance arises. This is an equation easily applied to a number of political movements, from Civil Rights to the fight against Prop 8., but what happens when this sentiment is applied at a far lower (and less heated) level, towards the simple experiences shared between two individuals? On this level, understanding feels far more accessible, the potential for achievement within easy reach. There may be a danger in this reliance, for understanding in its past tense (“understood”), is boiled down to assumption as well as agreement (and as another common adage warns: “ to assume makes and ass out of u and me.)

My good friend Claire once shared a story with me that she had classified as being a “core memory,” essential to the saga of our friendship (her version). As I walked over the Ballard Bridge in Seattle, 2750+ miles from her apartment in Ithaca, NY, we reminisced via cellphone. At that point about eight years had passed since the memory’s original occurrence. While Claire’s memory did ring a few dusty bells, it was not (and is not) a part of my “Claire and Jessie” lexicon. In fact, at this very moment, I cannot bring to mind what she had shared (though the memory of forgetting is crystal). I can recall how hurt she had sounded that the memory’s importance was not shared, as evidenced by my forgetfulness. However benign this hole in my memory had been, I couldn’t help but feel the weight of heart-rending guilt pressing hard against my chest. To forget was a transgression against our friendship, that the act had been accidental was irrelevant (if not worse).

Should it matter whether or not this memory ranked similarly high for me; should my ineptitude have affected the level of Claire’s esteem for the memory and its importance? There were (and are) many stories I hold dear, involving Claire as a key player, a fraction of which have presumably escaped her in a similar fashion. Though we’ve not spoken of that conversation since, I have little doubt that the memory has remained somewhat affected. As shared experience, much of memory’s strength is found in its perceived mutuality. When one feels as though a level of understanding and enjoyment has occurred in a particular moment, one hopes to retain that mutuality in memory, preserved. The seal can be broken in times of reminiscence, both solitary and social. In these times of sharing, revelations can occur: of both absence and (more troublingly) discrepancy. Is it the addition of temporality that sullies understanding, as being understood becomes assumption?

GS- Glass Soup

Jonathan Carroll creates a situation somewhat similar to Claire’s and mine in his novel Glass Soup (only Surreal, fantastical, and based in romance). Leni and Simon are two characters (former lovers) that die in the course of the novel, only to be reunited in death. GS establishes that death is not a stagnant realm. When one dies, s/he is inserted into a personal death realm, composed of all the trappings of their past life (materially and experientially.) Dreams are included in this system and are likewise crucial to the death experience. Individual modes of perception are key factors in the differentiation between realms. A tree in Simon’s realm would presumably be quite different than one found in a separate realm. Halfway through the novel, Simon finds a way to insert himself into Leni’s particular death (he must do so in order to save a mutual friend, long story very short.) It is worth acknowledging Leni’s emotional state within her death, which is one of extreme anger. Her current situation (death) had been wrongfully achieved (she’d been murdered by a deceitful lover).

When Simon first appears in Leni’s realm, she does not believe that he is “real,” because she had already come to realize death was in many ways a place of her making. She assumes that Simon, too, is a work of her creation, so she creates a second Simon in order to flex her abilities; “she conjured the Simon Haden she remembered and been together with in life.” (Carroll 189). This Simon (#2) is a compilation of her memory and her desire. The real Simon is able to bear witness to the discrepancies of Leni’s memory/imagination through the physical manifestation of #2; and he is no fan of her interpretation. One such discrepancy in particular centers on a request for avocado; this becomes an emotional “last straw” for Simon.

…his frustration spilled over when #2 asked for something to eat—maybe an avocado? Haden loathed avocados. Those strange green things that always reminded him of legless frogs…

“I hate avocados! I would never ask for one.”

When he said that, Leni looked at him outraged, hurt eyes and immediately began to cry. Why? What had he said? (Carroll 190)

It is then revealed (as Simon remembers) that one of the few romantic and intimate engagements the two had shared (in life and like—not love) had centered upon a sun-filled trip to an open-air market, a whimsical purchase (on Leni’s part) and theft (on Simon’s part) of two avocados, culminating in a surprise dinner of guacamole and wine: a product of Simon’s thoughtful creation. “’Ohhhh yes, I remember that day.’ He was smiling now, ‘You choked on a carrot stick.’” (Carroll 191) This response works to enrage Leni further. Again, Simon is left sputtering and confused. She lashes out.

“What, why are you so upset Leni? What’s the big deal?”

“…because it was my memory and my life. Now you’ve changed it and there’s nothing I can do about it, you bastard! Now it will always be the day I choked on the carrot stick and you hate avocados.” (Carroll 189)

She later expands upon her argument, that however badly she felt about how their relationship ended, “avocado” had come to represent the good times, the good in Simon, and (in some ways) reaffirmed a reciprocation of feeling and emotion (in Leni). When Simon fails to remember the evening and comes to belittle it in his recollection, that feeling of reciprocation became tainted. For Leni, her wondrous avocados had become pitiful carrot-sticks and the self-perceived image of her desirousness likewise became one of clumsy embarrassment. In many facets of our lives, it is understanding and reciprocation that what we seek, especially when it comes to relationships (of the romantic as a well as the platonic variety.) Leni feels as though Simon has devalued the worth of her memory, and he has done so through his lack of prolonged reciprocation. The revelation of weakness/detachment in an area of a relationship once felt bonded and strong can’t help but call other areas into question. Sympathy has a hand in understanding. With one look at its paired down definition—

1. agreement in feeling, accord

2. compassion

--one can easily see where Simon’s lack of awareness could be construed as a cold lack of sympathy, compassion, and accord. Leni feels isolated and lessened by this disparity.