read the things already

a place where words meet internet. here's wishing they met something else.

Sunday, November 3, 2013

It's Not You It's Me--Draft

Playing with Barbies--Draft!

Where Untitled Green and Blue set me thinking on social hierarchy in the Barbie-verse and beyond, Off With Her Head has a far more sinister tone, conjuring thoughts of murder and betrayal. Two nude TB’s stand in profile, the figure on the left (TBL) faces the right side of the frame in full while the rightmost figure (TBR)’s face angles slightly out toward the viewer. TBL’s left arm is extended out towards TBR. Composed of two separate panels hung flush, this slender plastic appendage makes the journey from left panel to right. The composition is dramatically lit; each figure throws a stark umber shadow upon a richly hued background (the burnt sienna surface all but glows). Lighting, placement, and title all work to fashion the beginnings of a story; one of peril and pursuit. It feels as though TBL approaches her unsuspecting twin with the darkest of intentions. Is a bloodless decapitation on the horizon as the title would suggest? Though each figure is relegated to a separate panel, TBL has bridged the gap. Her arm reaches to TBR for some unknown purpose, she appears to be closing in. The figures’ faces hold the usual semi-vacant expression. They flash their familiar and unthreatening smiles, seemingly ignorant of the dim scenarios in which they’ve been engaged. It is this aspect of apparent guilelessness that unravels the murderous yarn I’d begun to weave. The scene is reset, imagined threats removed.

Tuesday, January 8, 2013

Traces of Poe: A meditation on two particular tales

While preparing for What Remains: Traces of Poe (an art installation I mounted in conjunction with a colleague), I listened to audio books of Poe’s work in order to fully saturate my artistic focus with Poe-ness. As luck would have it, audio renditions of Berenice and Eleanora appeared almost side by side. When taken in close succession, these tales create an interesting juxtaposition. While Eleanora and Berenice involve a somewhat similar set of circumstances each is executed in a completely different key. Our respective narrators’ romantic lives hold certain traits in common (as does Poe): all three fall in love with his respective first cousin(s) all three cousin-lovers fall deathly ill. It is here where the similarities end and these stories diverge.

While Berenice is easily pegged as a classic gothic tale (to this untrained critic), full of madness, obsession, horror, and a bit of premature burial for good measure, Eleanora is not so easily classified. Though the narrator claims madness, the tale is no dark and broody slog through the dim corners of one’s mind. It reads as a bittersweet song dedicated to love, loss, and moving on. Yes, there are trappings of the supernatural as well as some cyclical thinking from a deeply devoted narrator, but these bits are not pervasive. Where Berenice is dark and claustrophobic, Eleanora is fresh and free moving (aerated and unbound) much of the action takes place outdoors in the idyllic “Valley of the Many-Colored Grass.” Where Berenice’s Egaeus’ obsession sends him spiraling further downward into the muck and mire of madness (towards a grotesque end), Eleanora’s unnamed narrator (UN) is able to let go and move on with seeming success. Egaeus is fixed in his despair.

Berenice involves cousins unalike in temperament, Egaeus (our narrator) is “ill of health and buried in gloom,” while his cousin is “agile, graceful, and overflowing with energy.”

“Hers, the ramble on the hillside/mine the studies of the cloister.”

Though UN alludes to similar leanings in his love (“artless and innocent as the brief life she led among the flowers”), he is not separated from her as Egaeus is from his Berenice; he joins Eleanora on her romps through the valley. Their love is realized amongst trees and flowers, star shaped blooms burst forth as if answer to their passion. When Eleanora passes seasons change to note the loss. Egaeus’ love is stifled, trapped behind closed doors from beginning to end. When Berenice is forced inside by illness; she deteriorates, unable to survive in Egaeus’ preferred habitat. As her health recedes, Egaeus becomes distraught and takes refuge in the once was. He proposes marriage though he can hardly stand Berenice’s state of diminishment. “Either the memory of past bliss is the anguish of to-day, or the agonies which are have their origins in the ecstasies which might have been.” A debilitating fascination with past-tense perfection bubbles up forcing him to execute monstrous deeds. In a trancelike state, he moves to possess her last remaining attribute. His obsession is total.

UN’s devotion does not move beyond the verbal (he is not consumed as Egaeus). Despite his vow to “[Eleanora] and to Heaven, that I would never bind myself in marriage to any daughter on Earth,” upon moving to the city he meets Ermengarde. “What was my passion for the young girl of the valley in comparison for the forever and the delirium and the spirit lifting ecstasy of adoration with which poured out of my whole soul in tears at the feet of the ethereal Ermengarde?” Though he’d sealed his vows with an invocation of damnation from the Alimighty (should he renege), our man marries Ermengarde all the same. This new love overpowers any fears of this self-administered curse; it is just that strong. What fate should befall this impetuous lover? Utter torment? Ghostly harassment and all matter of punishment from a slithery nether realms? No, no--freedom is his fate. “Soft sighs in the silence of night,” bring word of his destiny from on high: “sleep in peace. For the spirit of Love reigneth and ruleth, and, in taking thy passionate heart her who is Ermengarde, thou art absolved, for reasons which shall remain known to thee in heaven, of they vows to Eleanora.” With these stories laid side by side, it would seem acceptance is to be rewarded while stubborn stagnation is worthy of punishment.

These stories appear to have been concocted in conjunction with key points in Poe’s own romantic life. Berenice was written the year Poe was married (1835), Eleanora the year Virginia fell ill (1842). While it would (most likely) not be accurate to take the relationships depicted in Berenice and Eleanora (respectively) as direct representations of Poe’s own life and marriage, they do offer a window into Poe’s stance on love. It stands to reason these feelings could easily be applied to Poe’s own romantic life.

Egaeus worships his cousin’s vitality, so too did Poe worship Virginia’s youthful blush. After consumption hit, Poe wrote in a letter to a friend (according to Wikipedia): “...each time I felt all the agonies of her death- and at each accession of the disorder I loved her more deeply and clung to her life with more deliberate pertinacity.” Just as Egaeus became lost as illness struck, so too did Poe: “But I am constitutionally sensitive--nervous in a very unusual degree. I became insane with long intervals of horrible sanity.” Written seven years before Virginia’s own sickness, Berenice seems a bit portentous in a way, though Poe’s own “insanity” could not contend with the addled mind of Egaeus. In all his grief, Egaeus took to his pliers while pen and paper served to channel Poe’s passion. In fact his construction of Eleanora in 1842 reads as a sad but phenomenally healthy act of meditation, a lesson in letting go. Though UN devotes himself to the dead in a fit of passion and grief, time and experience allow him the chance to reconsider. In the end, he chooses life (and Ermengarde). Poe himself made some efforts in this regard: he had taken up a few extramarital correspondences of an intimate nature during Virginia’s illness, supposedly with her encouragement and blessing according to one such pen pal.

When he passed away in 1849, Poe had been engaged to remarry. Were she to be his Ermengarde, we may never know. Definitive answers are rarely available where both death and art are concerned. After passing some time with these stories, mulling and milling about at easel and keyboard respectively, I feel as though I’ve struck flesh, bone, and perhaps just a snippet of understanding. Caricature is rendered corporeal and the pedestal has given way to personhood. As a maker of things, things to be viewed and consumed beyond my grasp and life span (possibly)--those feelings of connection and understanding that bubble up from the artistic ether feel all the more valuable. It gives me hope for my own creations. To be understood (even just a little) can be magic.

Saturday, November 3, 2012

Mark Havens' Monster Factory review

JB: Oh but I do.

AC: Yeah:

JB: I wanna be just like you. I figure all I need is a lobotomy and some tights.

BJ: You wear tights?

AC: No I don’t wear tights. I wear the required uniform.

BJ: Tights.

AC: Shut up. --The Breakfast Club, 1986

With all pun-based kidding aside, wrestling is a hard sport to pin down. Oscillating between theatrical ridiculousness and skillful seriousness, the physical prowess of each player may garner respect but execution and performance often eliminate any trace of said gravitas. A visit to Mark Havens’ Monster Factory presents for our viewing pleasure the world of Amateur-Pro Wrestling, and the tumult between amusement and appreciation found therein.

A quick spin around Havens’ presentation of Monster Factory at Gravy Studios (a Philadelphia-based photography collective) immediately stirred a range of reactions and emotions, from pitying sadness to a scoffing elitism (shamefully) onward to pure craft-based appreciation. Fashioned using government grade printing techniques (with the aid of a defense contractor in the Midwest), a more trophy-like surface had been Havens' original vision but the medium proved difficult and ultimately too kitschy to favor over optimal image quality. This sacrifice of foot-noteworthy relevance has done Monster Factory a great service; each anodized gold aluminum plate carries the stark and smudgy with equal capacity. The tactile teeth the coarse arena rope stands in fine relief against the softened bronze bodies in motion, inducing an almost emphatic tangibility: one can almost feel the rope cutting into his/her own skin.

It is Havens’ sensibility and choice of material that allows Monster Factory to ascend beyond the sort of voyeurism which often accompanies both still and moving images of this variety. When a window into a new world is forged, the attention and awareness created by this opportunity is not always gilt-edged and golden; judgment creeps in through the cracks. I have often found minor league sport clubs a bit sad, dank arenas full of dreams half realized. So and so wanted to be a Major Leaguer but only made it to the Minors (if that); so and so must settle for a small scale audience and the mere chance to play the game. Perhaps it is this dual need for and lack of an audience that is especially disheartening; a semi-ridiculous sport is made that much more ridiculous by an absence of audience. It would be easy for my mind to continue to wander down the self-fabricated paths of the supposed let-downs of these anonymous athletes if not for Havens’ own method of approach. The ever shifting greenish, gold and grey metallic tones of Havens’ prints are downright poetic; these sparkling hues are able to drag even this far too judge-y mind out of the trash filled Fishtown gutters.

It is difficult to pinpoint the exact essence affecting this transformation. Monster Factory bears some tonal similarities to the tintypes and daguerreotypes of old; images which often extract feelings of somber reverence. However, content and composition break this connection; these are not the stiff postured portraits of old. One image centers upon two grappling wrestlers; a light skinned torso bends backward to the left side of the composition, met by a darker torso on right. Elbows point out and upward toward the left hand corner of the plate. These angled arms and bodies create diagonal lines, mirrored movements lithely stretching with a dancer’s grace. Two fists cluster amidst the corporeal press, their white knuckle grip a reminder of the true nature of the activity on display. In a small space between wrist and bicep, we are able to glimpse a small portion of the left hand figure's profile. Lips and nose meet this handhold, effectively softening the action once more. Slightly parted, the lips are not ridged in a grimace of determination. They are soft, relaxed, and practically inviting. A hand belonging to the figure on the right appears at the base of the frame, grasping the neck of its opponent. When taken in conjunction with the angle of the bodies, the hand's true mission becomes muddy; the purpose of this coupling oscillates between gladiatorial athleticism and impassioned intimacy. There is both softness and strength to the action unfolding.

Another frame appears to depict the same two wrestlers. Now parted, the left-hand figure (LF) stoops, gripping the ring with one arm and holding his chest with the other, while the right-hand figure (RF) stands at the ready in the background. Visible from the neck down, his splayed fingers reach towards LF almost tentatively. Despite the stippled belly hanging over the band of his lycra briefs, RF appears braced for action. With mouth gaping and posture bent, LF's affectation implies injury. However, the hand upon his chest rests lightly; it does not clutch or grab. The delicacy of this touch removes the viewer from LF's purported suffering; the event is dramatized and aestheticized once more. It is in this rift with reality that a sort of elevation may occur. These bodies in action become non-specific vessels, narrative spring boards. With the aid of a little imagination brief bouts of athleticism can stretch to epic proportions.

Havens is at his most dynamic with compositions including more than one human presence (however slight). In one image two wrestlers occupy the foreground, each facing the left side of the frame. One man has placed a hand on the other's shoulder, right arm raised to administer a pat of good sportsmanship. Hair dampened with sweat, their cheeks glisten under the intermittent arena lighting. A ring ascends in the background, graced by a single spot-lit figure standing with hands on hips, muscled arms on display. His/her stance is strong, commanding, and expectant. This event to which we bear witness is most likely far less dramatic than it appears, a simple moment between matches. However, the placement and carriage of this figure in the distance, when paired with the men in the foreground, creates intrigue; the potentially mundane is rendered mysterious. Another frame features a wrestler of indeterminate sex seated upon the mat. Upper-body covered by a one piece sleeveless bodysuit, the figure’s face is soft and hairless; Adam’s apple verification thwarted by neck positioning. Visible from mid-chest up; her/his upturned face is tense and somewhat pained. An arm descends from the top of the frame; its hand rests upon the side of the wrestler’s head and forehead. There is a godlike quality to this gesture, the arm drops down from on high in order to bestow...what? Perhaps the gifted and benevolent appendage has arrived to relieve this androgynous athlete’s suffering while simultaneously releasing the contender from her/his duty (as both wrestler and human-being) to struggle. This laying on of hand could also read as an act of absolution, effectively wiping the crumpled player clean of the shame and embarrassment generated both by failure and the general stigma associated with the sport. Whatever the case, the sheer potency of the touch and the moment created by it is undeniable.

Real-time witnesses to these dramatic exertions remain sparse to completely absent throughout Monster Factory. When an audience does appear in the frame, its members are bleached of identity; they are but small figures in small numbers, eyes often blackened and obscured by hard-horizontal shadows created by the ring’s ropes. The sweating, flinging, puffing, and peacocking all plays out to a seemingly dispassionate and aloof crowd; they sit at an almost royal remove from the ring. We have no entry into the thoughts and reactions of these anonymous onlookers; where interest, empathy, and narrative are sparked regarding our gladiators these bystanders remain a blank. In many ways this acts to augment the emotions already stirred within the gallery-going audience outside the frame. A sort of Big Bro/Sis protectiveness bubbles up in the wake of disinterest. Those images involving single wrestlers flexing, shouting, and posturing are not quite as affecting; the viewer’s teeth go un-sunk. That being said, as their numbers are few these images are effectively bolstered by the stronger frames. It could be argued these compositions provide a necessary respite from the fracas while also serving to document the theatrical side of the sport. Each wrestler has a character and a particular way in which s/he evokes said role. Perhaps these images are less successful due in part to the player’s own poor performance.

One image of this type emerges to provide an exception to the rule. A single wrestler stands center ring with wet hair falling about his shoulders; a slightly puckered mouth opens low to reveal a few off kilter bottom teeth. His eyes are two sunken holes, plucked and blotted by a shadow struck by a bit of rope in the foreground (from the ring, presumably); one bent and well-muscled arm crosses in front of him while the other hangs at his side, angling backward. The moment rests on a temporal precipice; it reads as both pre and post, before and after. However spare its contents this image is surprisingly affecting; it easily matches the vigor of the more complex compositions. Its vitality is generated almost entirely by attitude.

These dispatches from Life on the Mat bear relevance beyond the microcosmic back-basement sporting centers of North Philly. In many ways they embody our human desire to matter, to make a mark while playing out to a sparse if non-existent audience. These wrestlers fling themselves off ropes; they grapple and fight in tiny arenas a far cry from stadium lighting and an audience of millions via Pay-Per-View cable listings. Yet they appear to go forth with the same level of dedication to perform, cranked to eleven. Their ability to give their all to an empty room is a lesson to any person attempting to make their way in the world. In this way, the oft times pitiful and laughable (according to a judge-y curmudgeon like me) becomes commendable and relatable. As a somewhat unknown painter and draftsperson, unobserved endeavors are my middle name. Is my perseverance any more or less ludicrous? Monster Factory reflects back one’s own undertakings, revealing secret fuels stoking secret fires. While fame is not on my to-do-list, peel back the layers of generically bohemian ideals of truth, love, and beauty and I’m sure you’ll find a dark pitted craving for credit.

note:

[Havens’ later confirmed the wrestler of unspecified gender--Pretty Boy-- as male. I had initially deemed Pretty Boy a woman in a prior draft of this review. Rather than appropriately identifying PB’s sex at the outset, I decided to leave his gender unverified. Because the image creates the question, this quality adds something to the work. My own disclosure would potentially remove this aspect of the image from the discussion.]

Tuesday, August 9, 2011

Essay questions, yo

Why would I want a (free) studio:

For about nine years, my studio and bedroom have remained superimposed within a single realm. Less choice than necessity, this action originally begot by financial force has become an integral part of my studio practice. That being said, the home studio has its limitations. Many projects must be quashed out of simple respect for rented dwellings. Isolation is an equally regrettable result of such a practice. Such a state affects one’s emotions as well as the product of one’s endeavors. Studio progeny come to feel stifled and shut in. Though I hesitate to leave what has mostly worked so well, the promise of interaction through barter is quite inviting. In many ways, what I would I owe is exactly what I seek. Social engagement and artistic expansion are forces that flow in unison. This space stands ready to meet the needs left unanswered by my current domestic headquarters.

Out-reach!:

In this epoch of impending shortage, I often wonder what sort of art practice and aesthetic is born of scarcity. About a year ago (in addition to my painting) I started to create little message-laden bottles from the detritus of my consumption; I’d then scatter these slight containers teeming with poetry and drawings about the city. This simple effort towards artistic-recycling has morphed into something far more complex (for me anyhow). Not only do these votives fulfill a need to connect but they also create a platform for giving. While my paintings are stacked at home, longing for new homes and walls, these bottles are gladly set loose on the world. Through this residency, I hope to expand upon this fledgling project (perhaps link it more closely to my practice as a painter) as well as to create some workshops geared towards this sort of making.

Friday, October 1, 2010

fix for the last paragraph

These objects are not in the business of conclusiveness. Answers stifle upon premature arrival; inquisition is essential to discovery. It is inquiry that maintains a fluidity of thinking. Me? I am but a lone defender of imagination, both yours and mine. My goal is not to dictate, but to foster.

Besides, art need not be a drag.

Thesis: Final First Draft, 11 is a lucky number

There is a growing bleakness slowly swaddling this particular epoch of humankind; my generation is far too comfortable with the term “Apocalypse”. Rather than clutter my process with the density of distress, I allow art to be a true act of optimism in my life, even if what is produced is nor purely optimistic. Escapist as it may seem, the thing I love best about art is the plentiful cornucopia of possibilities it presents. My daily life is composed of a number of seemingly shock-less objects and habits; creating constructs an opportunity to expand and forge far beyond the trappings of the known and accepted. In many cases that which is presumed known is rediscovered in a fantastical new light.

As an artist privileged enough to be making work in 2010, where opportunity is vast and experimentation is commended, why would I constrict my heart’s content? Life can’t help but be limited; poverty limits us farther. The laws of both society and physics are to be followed, lest one suffer the consequences. In the second- dimension, such laws are not easily punishable or applicable. So why not take up this one chance and plunge forth into possibilities not offered in our own realm, the one called life?

This declaration of allegiance to the fantastical is my privilege as an artist of this epoch; it is also bit of a conceit.

These sentiments glisten and glow in the soft wattage of generality. Theirs is a vague glory; verbal ventures into specificity (of execution and effect) mostly die upon the page and tongue…and so I refuse. “Words fail! Words limit! Experience for yourself!” I cry. This response never goes over well. The phrase “cop out” emerges to rear its ugly and not so unanticipated head, as do the words “childish”, “flippant”, and (my favorite) “irresponsible”. Choices made in the heat of the making-moment become seemingly arbitrary in their unstructured push for possibility, once extracted from any effort towards explanation. It would seem that no matter how affecting these artistic vagaries may perform in practice, declarative matches for How and Why remain requisites. My quandary is in no way novel; the epic low-grade struggle of The Artist between words and wares long precedes this baby-faced millennium. More akin to repetitious trips to a crowded grocery store than a tumultuous10-year excursion from Troy to Ithaca, the task is brow-drenching all the same. My own explicative efforts have almost always fallen short of both adequacy and success. Inky droplets wrung from mangled missives stain these hands time and again.

Are these splashy sashays into imagination so light as to be content free? Can that which is born from a near monastic studio practice have much to offer the outside world and its inhabitants? Art is a form of communication, after all. If the artist and creator is loath to identify meaning within her work, how then can a viewer be expected to do so? This ever-maddening linguistic situation, of warring words and imagery, poses a paradox to my production. Be that as it may, the potential frivolity (and inaccessibility) of my artistic devotion is not easily digested. Expansion, with a dash of intimacy, is my prime objective; these intrigues of the imagination are meant as joint ventures. Without words, these products of secluded thoughts and actions are forced to teeter towards exclusion rather than invitation. If left in this fugue state of experimentation, indulgence may be only mine alone.

Dictionaries flip and offer me their contents. For years the word “surreal” has been under my clumsy employ, summoned dutifully for explanatory endeavors both great and small. It always seemed the best emissary to the oddball imagery born from my rampant acts of imagination. Of course the word had been produced with little conscious regard or respect for all that word implies. It was a term chosen more out of exasperation than laziness, I swear. Now a few years older and wiser(-ish), I’ve discovered that intuition goes a little farther towards actually accounting for my practice in action, as well as my verbal blockages. Random House has intuition listed as:

1. knowledge or belief obtained neither by reason nor by perception 2. instinctive knowledge or belief 3. a hunch, or unjustified belief

Initially these words combine to create a swagger—a sort of confidence despite nebulous conditions. The word knowledge works to assuage any wrinkles of concern creasing this crumpled brow, to squelch reason’s reproachful glare. Unfortunately, these words act as double agents, operating both for and against my argument. Belief does not belie truth, reason or sanity. As for hunch, well, need I say more? How can you trust a hunch to do the heavy lifting?

A year or two ago, while in the throes of an era far from digital technology and plastic (I was researching Renoir), I found my state disrupted when a good friend demanded that I watch a particular episode of Art:21. I protested, crying “Impressionism!”; she plunked me into a chair and cued up. As soon as the name “Jessica Stockholder” crossed the screen, a burst of recognition followed. A professor had recommended I look at Stockholder when I’d been going through a thoroughly embarrassing and brief installation phase. Though my current work is quite different than that of Jessica Stockholder, our sensibilities regarding creativity and creation seem quite similar.

What’s intuition? It’s a kind of thinking. It’s not stupidity…I think there’s a discomfort associated with trying to put (together) all those different ways…the brain works. I like to avail myself of that discomfort. (Stockholder, PBS)

Stockholder describes her artistic process as an act of “play”, a process of “learning and thinking” with “no pre-determinate end”(Stockholder, PBS). Her installations consist of everyday objects, and are heavily dependent upon lots of brightly colored plastic. In some cases the objects hold weightier metaphoric meanings. The piece she was working on in this particular episode involved freezers. To Stockholder, the freezers carry a “dual” meaning. On one hand they are “places of food” and food can be symbolic of “family, loving, giving”. At the same time the freezer is “cold” which related to withholding.

Her process of color arrangement is quite painterly. Her aptly titled #291 is composed of “acrylic and oil paints, couch cushions, plastic container lid, shoe laces, hardware, chain, plastic scoop and toilet plunger” (McSweeney, http://www.virginia.edu/); a blend of bright blues, oranges, pinks and greens that are both flat and sculptural. Though I was only able to get a digital glimpse of this piece; 291’s ’s object-ness has not been lost or leveled. I am taken in and out of the second and third dimension quite organically. A cushion hangs from the wall, with a segmented plastic container attached to the lower left side. Orange scoops are grouped, spilling out of this plastic container. A chain extends out from the left of the scoops as a blue toilet plunger sits on the right. At the end of the disc is a circle of what looks like metal but it most likely paint. The container-cushion configuration is painted in segments of bold, flat tones; thus aiding in the flatting of the total composition into a cohesive whole. Just as that particular area reads as flat, I’m brought back into the clever little scoops.

The objects move between actuality, representation/symbolism (at times) and sheer forms and fields of color. There are a few tiers of material function and interplay at work. 291pulls me from its formal elements out into a quirky narrative, and then back into its aesthetic composition cyclically. At times I see a little moonscape and/or Mars-Lander, complete with it’s own chained metallic moon/planet. As soon as I get comfortable with this landscape, the toilet plunger declares itself a toilet plunger and I am on Earth once more. Stockholder does not seek to fully control how these objects are perceived, though she is aware of their power. They provide formal pleasures while simultaneously pointing to the real world. She attempts to create another world of experience, fantastical and free from the mundane, out of thoroughly mundane objects. This transformation allows us to be transported, elevated.

…my impulse to make a work begins with my feeling that emotional life isn’t allowed room in the world. This feeling is personal to me and my history, but I think it is also a modern issue in that a lot of people share those worries and feelings. So my work becomes a place to make fantasy and emotional life as concrete and real and important as a refrigerator, or the room that you are in. (Westfall, http://bombsite.com/issues/41/articles/1576)

I’d say there are two major differences between Stockholder’s work and my own. First, I do not stray too far from the second dimension. Although I utilize a variety of common materials in my craft (from jeans to table tops), the predominant amount of my work’s action occurs as surface-focused lines and color. “Real-world” materials are essential to my studio practice but the hierarchy of importance between object, representation and form is balanced somewhat differently than Stockholder’s. I don’t believe a two-dimensional art object can be taken without some consideration to matter and material. A painting refers to at least two realities: material and representational. As crucial as this idea of materiality and recycling is to my work (and life), it is not the sole epicenter of meaning.

The second major difference between Stockholder and I is that make use representational imagery, while she avoids it.

For me, to the extent that the work is abstract and not literal or literary, it is freed up to say something. I feel trapped by the literary. I think I would feel my work more subject to degradation or emptying out if I were making figurative work. Things that are abstract have the possibility to include different ways of thinking. (Westfall, http://bombsite.com/issues/41/articles/1576)

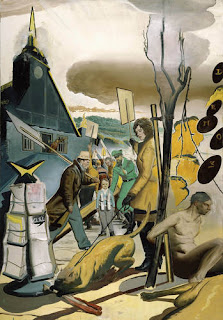

While Stockholder fears “figuration” would lead to limitation, I’d argue encroachment is not inevitable. One can use representational imagery in a non-specific, non-literal way. The people I paint are both unreal and totally real. Stockholder refers to the literary and literal in conjunction to figuration, I do not think that’s an inevitable anchor; it simply depends on the artist’s ability to allow for specificity beyond intention. Neo Rauch is an excellent example of this sort of practice: the use of representational imagery free from the constraints of straight narrative. In his article regarding Rauch’s interesting ascent into the “illustrious line of contemporary German artists,” Gregory Volk makes flagrant use of the words “maybe” and “might.”

Maybe [Tal] was meant as an ironic send-up of the former East-German government’s obsession with athleticism as a symbol of socialist prowess—but then again, maybe not (Volk, 140)

[Rauch’s paintings] might be triggered by details in and around Leipzig, or by childhood memories and, as he has occasionally indicated dreams, but their reach is in a collective past toward a speculative dream. (Volk, 140)

Volk is careful to keep his tentative translation of Rauch’s work in an amorphous state, though the imagery is well defined. That Volk is hesitant to charge full-force into a detailed assessment metaphor and meaning is a care I greatly appreciate. An application of steadfast subtext to each and every figure and symbol would stand in opposition to Rauch’s practice. When asked “about the meaning of his characters”(Volk, 142) at particular public engagement, Rauch “candidly admitted that he couldn’t always say for sure, but sometimes his figures are there simply because the picture requires it”(Volk, 142). Volk describes Rauch as abstractionist as much as a realist, “developing and positioning figures as much as an abstract painter works with basic formal elements”(Volk, 142). It’s not that the work is devoid of meaning, limited to pure formalism.

His symbolism, if indeed it is symbolism, is too hermetic, his references too complex…so you give yourself up to his paintings, approaching them with something of bewilderment. (Volk, 142)

Rauch’s Demos, at first glance, certainly emits a sort of Socialist mustiness. A number of sign wielding protesters spill back into space, a soldier in green makes a grab at a small child who looks directly out of the composition. The coloring is a bit paired down, compared to Rauch’s other works. It is the female figure at the center of the composition that drags me out of such a literal, slightly political reading. She is dressed in contemporary clothes; she wears black leather high-heeled boots and what looks to be a fashionable yellowish-tan overcoat. Her hair is stylishly layered; she holds a leash in one hand, and a sign in the other. Her dog pulls at the leash and bends to chew at a strange bone; a canine echo appears at the right hand corner of the composition in the form of a hind leg. The letters D-E-M-O-S trickle down the right side of the composition in separate discs; the discs hover above a naked man tied to a tree. Rauch’s paint handling is both tight and lose, detailed and cartoon-ish. Though Demos is teeming with imagery, I hesitate to delegate meaning for the very reasons provided by Volk: Demos is far too complex to pen in. Why shackle a dream?

Narrative structures rise and fall with ease before a Rauch or Stockholder alike. Though language becomes essential to how we interact with an art piece, it must be used with care. We rely heavily upon it, despite precariousness. It’s simply important the viewer recognize what’s been lost in translation. “In seeing, we typically substitute an appropriate language for the actual object in order to facilitate our ‘seeing’ of it – our language screens the object, it’s the grid that structures our perceiving.”(Art in Theory, p. 891) Mel Ramsden and Ian Burn (members of the Art & Language collective), specify ‘content’ as one ‘language’ of perception. When we attempt to interact with the piece, we are really interacting with the word, and also the concept of ‘content’. It perches on the edge of our thoughts, its gaze always piercing our analysis. Rather than interacting with the piece itself, we interact with an entirely different entity. What we define is ‘content’, content’s existence and content’s meaning. These findings are then related to other art pieces, and other forms of ‘content’. ‘Content’ itself can be broken down farther into various types and versions. Have we succeeded in our interaction with piece, as mediated by this concept?

Just as my right arm tenses and coils in preparation of its much- deserved ascent into a glorious fist pump of language-defying victory, muscles relax and straighten for mine is a false triumph. Whatever constrictive properties words may possess, my beloved representational images are likewise plagued. A non-verbal, two-dimensional depiction of a bowling-pin is equally at risk of absorption sans metaphorical mediation as its alphabetical counterpart. Bowling-pin has been visually identified, categorized and catalogued; we move on. In this way words and images run parallel rather than perpendicular; their function is similar. Both words and images are receptacles for meaning; these meanings are far less concrete than we’d like to acknowledge. Language is slippery; the concepts, truths behind its scrawl-y framework are more numerous than we’d like to concede. To fully access all that is found therein, we too must be lithe. This newfound fluidity may puff up or puncture depending on the angle of application. We are beings that enjoy systems, order and certainty. It is when those solid tenets of our reality are shifted that chaos ensues. It is imagination (and the ability to Not Panic) that negotiates this supposed divide between images, words and meaning (“knowledge beyond perception”).

The role of imagination cannot begin and end at a picture’s point of inception when freedom and possibility is the goal. For however high it feels I soar, buoyed by fantastical choice making, the ground is much closer than it appears. My wildest, wordless machinations must inevitably exist within the limitations of human experience. Though I may attempt to extend beyond my own perspective, the totality of such a measure is quite difficult to achieve. Even my temporary scapegoat for meaning (intuition) suffers a similar fate. How could we ever truly break free from our perceptions in pursuit “knowledge” and meaning? Here in Microsoft Office, knowledge itself if described this as “familiarity or understanding gained through experience or study.” Even if there were golden bushels of truth (and justification) to be plucked from temperate and untouched fields, with what hand could we employ for such a task? The successful achievement of utter possibility does not begin and end with me; I am disturbingly finite and far less wacky then I once thought.

This revelation is not an act of artistic deflation; it is a simple discovery of what it is to be of this world, to make work of this world and ultimately how said works can/will operate within this world. Stockholder’s aforementioned refrigerator is able to operate under many different guises beyond “refrigerator”. This ability is afforded “refrigerator” through words and imagination. Words provide the grid; imagination holds these words in check. “Refrigerator” can then move from “cold” to “withholding” with ease, while the object’s locus denotes domesticity. Though Stockholder does not claim allegiance to a single allegory by which the viewer must abide, she has most likely constructed a few of her own. In my own adamant refusal to verbally impinge upon the viewer-experience, I have denied myself the all too important opportunity to experience my work as a viewer. My freedoms have existed in action, not absorption.

The body of work to which this simple passage is found delicately stapled was executed as an effort to recognize and to harness the dual importance of artist and viewer in these flights of fancy (not sure I like this phrasing). While unfettered creativity is still essential, identification is no longer my foe. Counter to past concern, imaginative potential has not been compromised in this heady undertaking. A cycle between words and imagery was easily and organically established, between action and assessment. A number of numbered “thought-diagrams” were constructed in conjunction with two-dimensional “illustrative” compositions. Some diagrams precede their compositional counterparts, while others step in at the middle and end of production, respectively. At times the creamy off-colored squares resemble simple drills of word-association while others go a bit deeper. Semi-conscious observations otherwise ignored stand to be counted in sprouting bursts of verbal digressions. Their function is neither one of interchangeability nor one of opposition. They are imaginative investigations in their own right.

Drawings, diagrams and other incidentals combine to provide a visible progression; each advancing object/element is composed of preceding parts. These objects are not in the conclusion-business. Answers can stifle with premature arrival; inquisition is essential to discovery. It is inquiry that maintains a fluidity of thinking. It is not my wish to be dictatorial, but to foster. Though my curtains of creativity are pulled, and no thoroughly disappointing gentleman in a cravat and striped pants has been revealed, I still hesitate to assign meaning within this treatise. My drawings, diagrams and other incidentals combine to provide a visible progression. Each advancing object/element is composed of preceding parts and these objects are not in the conclusion-business. Answers can stifle with premature arrival; inquisition is essential to discovery. It is inquiry that maintains a fluidity of thinking. A dictator I am not, but a lone defender of imagination.

Yours and mine.

(Art need not be a drag, after all)

Bibliography

Westfall, Stephen. “Jessica Stockholder.” Bomb Magazine 41 Fall 2002: 92.

Volk, Gregory. “Neo Rauch: Time Straddler.” Art in America: International Review 6 June/July: 10, p.138-145.

Burn, Ian and Ramsden, Mel, “The Role of Language” in Art in Theory 1900-2000: An Anthology of Changing Idea (ed.) Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (Blackwell, 2002), 891-3.

Harrison, Charles, and Wood, Paul. Art in Theory: 1900-2000. Oxford: BlackwellPublishing, 2003.

Rauch, Neo. Tal, 1999. Private Collection.

Rauch, Neo. Demos. 2003. Private Collection.

Stockholder, Jessica. #291. 1997. University of Virginia: Art Museum.

“Play.” Art 2:1:Season 3. . PBS. 2005.

Random House Dictionary. New York: Random House, Inc 2010.